Brian McLaren: I think the theological often subverts a healthy emotional response. So much of our theology is part of the problem, and I don’t say that glibly. I think a lot of our theology arose to solve real problems of the past, and now we’re living with the unintended negative consequences of many of those solutions.

Brandon: Hi, I’m Brandon Nappi.

Hannah: Hi, I’m Hannah Black.

Brandon: And we’re your hosts on The Leader’s Way, an audio pilgrimage from Berkeley Divinity School, the Episcopal Seminary at Yale University.

Hannah: On this journey, we reflect on what matters most in life as we talk about all things spirituality, innovation, leadership, and transformation.

Brandon: Happy summer, Hannah.

Hannah: Happy summer, Brandon.

Brandon: I mean, it’s not officially summer, right?

Hannah: As far as our academic lives are concerned, school’s out.

Brandon: Yeah, after graduation, it’s summertime. Mm-hm. Yeah, do you have any favorite things that you like to do in summer?

Hannah: I really do. Back in California, it was going to the beach. Still in New England, I really love going to the beach. But I also love, love, love taking the dog on hikes at the different Connecticut state parks. What about you?

Brandon: I mean, I want to just love on Connecticut for a second. A really big fan. There’s great hiking in Connecticut. We have mountains. Like, if you’re a mountain hiker, we have that, right? We have the Appalachian Trail. We have Bear Mountain. We have a lot of rails to trails for those folks looking for flat places to walk in wooded areas. We’ve got beach. We’ve got great universities. I just love Connecticut. We have this lovely little lake in town that I like to go and play guitar.

Hannah: Oh, nice.

Brandon: There may have been some times when I worked from the lake last summer, just sayin’.

Hannah: Isn’t my virtual background on this Zoom call stunning?

Brandon: But for me, the best part of summer is just walking. I love taking after-dinner walks, in Italian it’s called the passeggiata.

Hannah: Oh, that’s a good time of day too in a Connecticut summer because it is pretty hot and humid in Connecticut. That’s a really beautiful time of day.

Brandon: It gets hot and humid. It sure does. I love the passeggiata as … a time to connect with friends and family. We have our ritual; folks in my house know that I take a walk after dinner, so they join me and we have just some time, reflection and talking, catching up. And then if I have a solo passeggiata, walking is really where I do my best praying, walking around the neighborhood. And I wonder what my neighbors think of me sometimes. I’m pretty sure … that I’m moving my lips and talking out loud to myself.

Hannah: “There goes the crazy man.” Yeah, I can’t remember if I’ve said this on the podcast before, but I do feel probably the most connected to God when I’m just surrounded by nature. And there are such good places for that in Connecticut.

Brandon: Well, I feel like this conversation really requires a certain amount of prayerful grounding because we talk about tough things. We talk about the many ways in which the world is broken. And of course, the urgent challenges of the world call for wise prayerful action.

Hannah: Yeah, it feels very appropriate for us to be talking about the hard things since we talk so often about hope on this podcast together. And if you haven’t already, go listen to our episode that we were guests for on the podcast “And Also With You,” where for like an hour, we just camped out there on the idea of hope and what it is, what it is in the Christian life. And if doom, which is our subject for today, needs anything from us, it’s hope. We have to hope in the face of doom in responsible ways, but there are different ways to despair in the face of doom. And what we get to do is hope.

Brandon: And I think there are near infinite ways and reasons to be hopeful in the world, but those ways can be obscured sometimes by the reality of the struggle and the fragmentation and the suffering and the injustice.

Hannah: So yeah, the bigness of the problems.

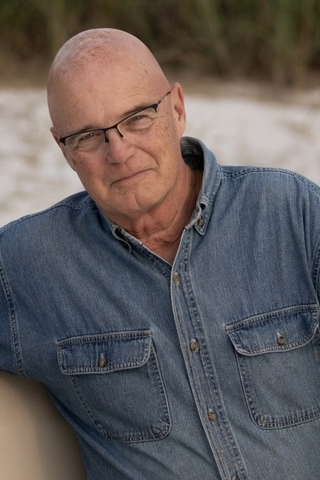

Brandon: Yeah, yeah. I mean, this was a hard conversation, but a really important conversation. I think ultimately a hopeful one nonetheless. And Brian McLaren is such a wise guide and he’s been a pastor, author of many, many, many books, musician, composer, and currently teaching alongside Father Richard Rohr in his living school. And so he was just so gracious in making some time for this conversation. Of course, he has a wonderful new book on doom and the way forward through it. Hope y’all enjoy the conversation.

Brandon: Brian McLaren, we’re so thankful that you’re here on the Leaders Way podcast.

Brian: I’m so happy to be with you both.

Brandon: So I have a funny story to tell you, Brian, as a way of kicking off our conversation. Your beautiful new book, Life After Doom, Wisdom and Courage for a World Falling Apart, has been sitting on my coffee table for about a month now. And I have been really, really enjoying it and reading it nice and slowly. And my wife one day saw it for the first time and came to me with a very serious look on her face. She said, “Are you okay?”

“Yeah, I’m great. Why?”

She said, “Because there’s this book about doom on the coffee table and I’m pretty sure it’s yours. Do we need to talk?”

And of course, the answer is “Yes, we do need to talk!” And so I wonder… Doom is a really big word, but one that feels really appropriate for these times. But I wonder how you came upon that word. And if you could tell us how you got to that word and the origin story of the book.

Brian: Sure. Well, first, so happy to be with you. And please send my apologies to your wife. I hate the thought that I made someone worry. So let me give you a short answer to that question. And then if you want, I could give you a bit of a longer one. But the short answer is a whole lot of us who are paying attention to reality, not just to one little slice of it, but if we’re listening to people talking about climate change and the environmental crisis and the rise of authoritarianism and resurgence of white supremacy and concentration of obscene amounts of wealth and power among a very small cabal of oligarchs … you start paying attention to all of these problems, and you not only feel how intense each of the problems are, but you realize that each of the problems makes it harder to address and resolve the other ones. There are a whole lot of us who, when we start paying attention to that, feel the sense of doom creeping up our back between our shoulders. And I have felt it. You keep things at bay sometimes. And sometimes you feel that keeping this at bay is taking more energy than actually facing it.

So that’s why I decided to just go ahead and put that word in the title to try to name the problem that we have a feeling of doom, many of us, and then to also put some promise in the title that once that feeling comes over you, what do you do with it? Is there a way to live and maybe even live well with that feeling? So that’s the short story.

Hannah: Yeah. So tell me, if I’m feeling the doom, what kind of answers or suggestions or solutions do you have for us? I think a lot of us are increasingly feeling that sense of doom you’re describing.

Brian: Yeah. Well, I had a really nice logical outline for this book. And once I started writing it, I just had to throw the outline away. And I ended up designing the book, each chapter title being a kind of little mantra or a kind of little sort of self-imposed moral guideline to help us deal with doom. They naturally kind of shaped in what people often call the Journey U, or the U-Shaped Path of Dissent. And so we start with “letting go.” And that largely means letting go of our feeling of control, letting go of our assumptions about what normal is, letting go with comforting illusions that are now looking less and less believable, and then dwelling in a place we might call “letting be,” where we try to, instead of fix the reality that we’re trying to face, we actually try to let it teach us, and let ourselves marinate in it a little bit and see how we’re actually changed when we stop trying to get back to the old normal. And then comes a “letting come” phase, where new possibilities emerge because we’ve gone through that descent and that sort of dwelling at the bottom, so to speak. And then I think we feel a sense of freedom after that. So I call letting go, letting be, letting come, setting free as a kind of emotional journey that I think we’re going to have to go on if we want to experience some kind of good life in the presence of struggle and uncertainty.

Brandon: I love the language that you use. And I think this is particularly a gift of yours that you can lead us into that You-Shape, so you could lead us into the descent as a compassionate guide without taking us to the point of despair. I mean, this is really, really artful. I mean, you talk about collapse, and it’s actually a word that I haven’t heard a lot of folks talk about, but it does seem really apt. And you describe these four potential scenarios of collapse that we face, that we could face as we sort of address the doom of our world. I wonder if you can play those out. I really found that evocative.

Brian: Well, I’m glad, Brandon. Thanks for that. I feel like it’s one of the main contributions I think this book will make to the ongoing conversation about the mess we’re in. Some people call it the meta-crisis, the poly-crisis, the multi-crisis. But I propose four scenarios. One is called collapse avoidance, meaning that we are perched on the edge of a kind of environmental collapse. We are pushing our environment past its limits to maintain anything like the environment we’ve known for all of human history. But that environmental collapse isn’t our most immediate problem. As the environment destabilizes, we face economic collapse. We face political polarization and collapse. We face a whole other range of what we might call a civilizational collapse. We might be able to avoid that. And I think most people would say, “Well, that’s the best case scenario. We could avoid collapse.” Later in the book, I suggest there are some downsides of that short-term collapse avoidance unless we do it in a really sensible way. So collapse avoidance.

Second is collapse rebirth. There could be a kind of collapse of our existing civilization structures and so on as we know them. And then there could be a rebirth after that collapse. You know, the fact is this has happened so often in the past. We talk about the collapse of the Roman Empire. The British Empire. The collapse of feudalism into the birth of capitalism. Well, who should be surprised if our current structure doesn’t have a shelf life too? So collapse avoidance, collapse rebirth. Third is collapse survival. Among people who study this sort of thing, they tend to say there’s a kind of baseline of human survival that it’s possible the future could lead us to. It would be a reduced number of human beings and a far less, to us, comfortable and complex kind of civilization. But that’s collapse survival. And then fourth is collapse extinction. I don’t think there’s anyone who’s taken seriously who thinks we’re talking about the extinction of all life. But there are significant thinkers who feel that the risk is far from negligible, that we couldn’t drive ourselves off the planet. And maybe a significant portion of land and sea-based life.

So there are some very scary scenarios out there. So those four. And here’s the thing, our minds tend to go toward the best or the worst. The best being, “Everything’s okay. We don’t need to worry about it. And we can return to our previously scheduled apathy and complacency.” Or “It’s all over. There’s no hope. There’s nothing we can do so we can all return to our previously scheduled apathy and complacency.” And one of the things I hope by giving four scenarios that we can do is subvert that trick of our brains that always wants to resolve things in a way that requires nothing of us.

Brandon: I think this is just maybe the pastor in me, Brian. But I’m wondering, what was it like writing the book? You had to go to some pretty intense places and contemplate some really terrible realities. And I’m just wondering, what was that path like? How did you care for your heart? You’ve written many books, but I wonder if this one felt different in any way.

Brian: Well, you are talking like a good pastor there, Brandon. Because … so a bit of backstory. I wrote a book that came out in 2007, I think it was, called Everything Must Change. And that was my first book where I indulge in a curiosity I’d had, sort of a haunting curiosity I’d had since way back in my 20s. And the question is, what are the world’s biggest problems? And my kind of theological train of thought here was that I’d been trained like an awful lot of conservative Catholic and Protestant Christians to think that the primary focus of Christian faith was where you go after you die.

And I think a whole lot of people are way beyond that now. But there’s still a surprising number of people. That’s still their default mode. This is what Christianity is for, to resolve that question. And I had come to believe that Jesus’ actual primary message, “The kingdom of God is at hand,” was about what goes on in this life. That anything he says about afterlife is to draw attention back to this life.

So that raised the question, well, what are the biggest problems in this life? If God is concerned with the healing of the earth and all of its creatures, what’s going on? And when I came to the end of that research project, I had deepened my understanding of global crises, and I saw a terrifying question. And it was so terrifying that I didn’t feel I could just throw it in the last chapter and walk away. It felt like that would have been very irresponsible. And that question was, is our current global civilization salvageable, or is it not salvageable? Another way to say it is, should we keep trying to save our current civilization, or should we try to start planting the seeds for a civilization that could arise from the ashes of this civilization’s collapse? Now, some people think, what a misanthropic and depressing and gloomy and horrible question. But if someone says that too glibly, it means they haven’t really paid attention to the cost to human beings, past, present, and future, and to the earth itself from the civilization– of providing this comfortable civilization in which most of us take for granted as normal and normative– it’s highly abnormal. That question sort of has been hanging with me for 15, 16 years.

Hannah: Yeah. Well, and without the tools, how do you look that problem dead on?

Brian: Yes, that’s right. And so it turns out there are a number of people who are grappling with these questions. And so, Brandon, when you asked, “How did I handle it?” Well, I started reading and listening to these people, none of whom I agreed with then or agree with totally now, but who I felt were saying things that people don’t want to hear that need to be taken into consideration. And there were days where I would just get up from my desk and say, “I can’t really take this anymore.” And I would just have to go take a five or six-mile walk and just process and be quiet and notice trees and do all the things that we do to try to regulate and get out of our … we often talk about doom scrolling, but there’s also a kind of thinking where we just run in circuits and we can’t get out of it. So yeah, there was a good bit of that.

Hannah: Gosh. Well, I wonder if you can talk a little bit more about the way that spiritual life is involved. You led us through this amazing U-shaped process of how we can be thinking about this, how we can experience this, how we can kind of look at the problem and deal with it. Where does the emotional intersect with the theological?

Brian: Yeah. Yeah, what a good question, Hannah. I think we’d probably all three of us agree, if we just answer that in a descriptive way, I think the theological often subverts a healthy emotional response. So much of our theology is part of the problem. And I don’t say that glibly. I think a lot of our theology arose to solve real problems of the past. And now we’re living with the unintended negative consequences of many of those solutions.

So for example, there’s a whole field of Christian theology called eschatology. And there are two main forms of eschatology. One of those forms says that God has a joyful and loving future for planet earth. And the other says, “God can’t wait to destroy planet earth, burn it up.”

Hannah: It’s all going to burn for hundreds of years.

Brian: Exactly. And all God wants to do is suck out the human souls and take them up to heaven because God never liked all this matter anyway. God just likes spirit and souls and that sort of thing. And the truth is, I think both of those eschatologies are unhelpful. People might be surprised to hear me say that. But I think believing that the future is determined either positively or negatively, either of those eschatologies is a very dangerous thing to put into human hands.

Hannah: It sounds like it’s a question of agency.

Brian: Exactly.

Hannah: Like as human beings, we need to be awake to these problems. We need to do something.

Brian: Yes. Yes. Many years ago, my own sort of reading of the Bible and a lot of my theological assumptions were shaken and challenged by the South African theologian Alan Bosek, who wrote a book that was really an exegesis of the book of Revelation in the light of apartheid in South Africa. And it was called Comfort and Protest. And Bosek made this comment about the prophets in the Scriptures. He said, “Prophets aren’t foretelling the future. They’re warning people.” And they’re saying, “If you keep doing what you’re doing, here’s where it will lead.” If there’s a just God in the universe, right? “Here’s where it will lead if you keep doing this.” And then he says, “The purpose of warning people is so that your prediction will not come true.” And the classic example of this is the book of Jonah. Jonah goes and says, “You’re going to be destroyed, Nineveh.” The purpose of saying that is for Nineveh to say, “What are we doing? We better change our ways.”

Hannah: Reroute.

Brian: And of course, yeah, exactly. So that’s what we need, I think.

Brandon: So I’m connecting a couple of dots. I was thinking as you were describing the current calamity and scenario of the world that our nervous systems aren’t designed in some ways to honor such eventualities. This kind of mass global calamity isn’t how our nervous systems were calibrated. And I was also thinking, neither is our theology calibrated to this level of impact as well. And so I guess the question that’s emerging for me, if our nervous systems need to catch up to what’s happening, if our theology needs to catch up to the challenge of the moment, what kind of prayer life do we need to develop to meet this moment? Because for me, prayer is where the nervous system and the theology meet in practicality. It’s where the rubber hits the road, at least it’s been for me in my life. And so I wonder, what sort of spiritual life do you want to invite people into to really meet a moment like this?

Brian: Oh, Brandon, I love that question. And I’m so tempted to go off on a bunch of flights of fancy about elements of the question. But because it’s a very practical question, let me try to say something very practical. I think the kind of prayer we need at this juncture is what we might call contemplative prayer. And by contemplative prayer, I mean prayer that is less trying to control outcomes and is more trying to both regulate and seek transformation of the structures of our being. Because when many people think of prayer, what they think of is, How can I get God to intervene and change the world to be more to my comfort and liking? And it seems to me there’s another kind of prayer that says, How can I face reality and how can I open myself to the kind of transformation that will be needed to live well in the actual reality that’s unfolding? That is a very deep and profound kind of prayer. Thanks be to God, we have centuries and centuries of that kind of prayer in our tradition. But many of us have grown up in church cultures where that sort of prayer is almost unknown. And if I could just give a quick example, I think the place where this kind of prayer first really emerges in a powerful way, apart from in the life of Jesus himself, is in what we call the Desert Fathers and Mothers or the Desert Sages.

Hannah: I was hoping that’s what you were going to say.

Brandon: We were going to cancel the podcast if you went in another direction.

Brian: Well, when you think about it, the Desert Sages arise in a collapsing empire.

Hannah: Absolutely.

Brian: The Roman civilization is collapsing, and there are two dimensions of it, or many dimensions, but here are two. One is that the church, in the early stages of the collapse of the Roman Empire, the church is co-opted by the empire to help it survive a little bit longer. And the church becomes domesticated by the Roman Empire. And there are people who are so devoted to the core of their understanding of gospel and presence of the Spirit and Christ in their lives that they say, “We don’t want to be part of this institution that has been corrupted and is making– where our bishops are making ugly deals with the emperor. Let’s go out in the wilderness and let’s create some little communes there where we can try to keep this thing going. Because we know now that the church will persecute anyone who doesn’t submit to the emperor and doesn’t play by the game.” That’s one dimension. The other dimension is the Roman Empire is falling apart. Its enemies are invading from the north and the northwest and the northeast. And “If we want to preserve any kind of learning and we want to preserve a safe way of life, we actually have to protect it from the collapsing empire.” And so you have one version of that happen in the North African desert and in the desert of the Middle East. And also you have it happening in Ireland and among the Celts. And other places as well.

Hannah: I forgot what we were even talking about for a second because it was like story time. I was in my happy place thinking about the desert situation. He stopped talking and I was like, “Why?”

Brian: And those desert sages, they inhabited other ways of prayer. They inhabited other ways of prayer. Yes.

Hannah: Oh, yes.

Brandon: Well, I’ll take you, sadly, Hannah, from your happy place really quickly, because I think there’s an important lesson. Help us learn it. I’m not sure exactly what I’m pointing to, but we recently had a conversation about Christian nationalism on the podcast.

Hannah: And we talked about the prophets.

Brandon: And we talked about the prophets. Yeah. So, gosh, are these conversations needed these days? And the move to unite empire and the gospel and what gets lost and who loses when we do that. And there are a lot of very devoted faithful Christians who believe that empire and Christianity are to be seamlessly woven together. And I wonder what gets lost and who loses in your mind when that happens.

Brandon: Yeah. Yeah. Well, the first thing I’d say is that the word empire is a very good word because it brings us back into Jesus’ day, the kingdom of God versus the kingdom of Caesar, the empire of God versus the empire of Caesar, the arrangement or way of life or economy of God versus the economy of Caesar. I think today, if we want to be specific, we talk about capitalism and we talk about white patriarchy. And very often it’s white Christian patriarchy. And there are other things we would talk about too. If we were in India, there would be a Hindu version of this. And if we were in Saudi Arabia, there’d be a Muslim version of this. But for many of us, it’s a white Christian nationalist patriarchy that is this struggle that we’re facing. And this is the irony. We’re having this conversation at the beginning of Lent. Once again, in another year, we go through remembering the life of Jesus that leads to Holy Week, which is a week when the empire arrests, imprisons, tortures, and executes someone who seems to not submit to it. And this is the constant challenge. And before the arrest comes, criticizes, attacks, persecutes, mocks, does everything they can to discredit what doesn’t fit in.

This is where I think we’re … in different parts of the world, we’re seeing this in a super obvious way. To me, I’m Protestant, but I’m a huge fan of Pope Francis. And I feel like you can pretty much look at the Catholic Church around the world as those that are trying to follow Pope Francis into some deep and needed change and those who will oppose Pope Francis to the point of calling him a heretic and apostate, even though he’s the Pope, which has a thousand irrationalities in it. But you sort of see the religious world making its choice in the Catholic world.

And in the Protestant world, we see it very obviously, I grew up in white evangelicalism, we see it very obviously, they are making their choice. 80, 81% of them are making their choice. Let’s hope it’s a few percentage points less this time around.

Hannah: Well, I was going to say in America, it’s bubbled straight to the top in our political life. And I think that’s been a point of reckoning for a lot of people.

Brian: Yes. And if I can say something, I have found refuge in the mainline Protestant world, right? But the mainline Protestant world is not acting like we’re in an emergency. Because it’s just they don’t have too much of that in their recent memory. In a certain way, there is a kind of complacency in the face of what’s happening that has its own serious set of problems. So this is why I think there’s just this important work. We don’t want people to panic, but we also don’t want people to coast along.

Hannah: Yeah. Yeah. I was just thinking about how I think culturally, we’re so uncomfortable with not feeling happy that that provides us with a lot of problems and this fits into that box perfectly. I was wondering if you could give some practical advice to our listeners who I’d imagine some of our listeners don’t feel very informed about things like the climate emergency or white Christian patriarchy, or … you name it. I’m wondering if you have advice for that group of listeners. And I’d imagine you have a lot of listeners who are like, “Yeah, I’m worried about these things and I’m squishing these worries into the back of my brain because I don’t know what to do.” As an individual or maybe it’s not an individual thing, just what do we do with this?

Brian: Hannah, I think that’s such a perceptive question. There are some people who have read advanced copies of the book or who’ve heard about the title and they say to me, their first reaction when they saw Life After Doom was relief because to see the word “doom” means finally somebody is taking seriously what I feel in my bones. Right? There are other people who think, “Oh man, he’s gone off the deep end. He’s become a cuckoo,” because their assumption is everything’s going to be fine and all the rest.

So the people who feel that everything is going to be fine, part of me feels like I don’t have any advice for them because I think there’s already enough evidence around them to tell them things aren’t fine. What’s going on … if they live in the United States. But it’s the same if they live in Brazil or in Argentina or in Poland or in Italy or in Germany. There are a lot of signs that what’s going on is not fine. We’ve never been in territory like we’re in now or in some countries like Germany, they haven’t been in this territory for 90 years and that’s a very bad sign. Right? If people aren’t paying attention to the environmental crisis, it’s because they belong to a community; it might be the community of people who watch a certain cable news station or the community of people who listen to a certain guy on AM radio or whatever. They’re part of that community, and they’re finding comfort and solace in that community whose identity involves calling all of this a hoax or whatever. Anything I say, they’ll just see me as people who are part of the hoax. Right? So to some degree, people who think we don’t have a problem, I just want to say, “God bless you. Have a nice life. I don’t think I have a lot to offer you.” But in three or five or seven years, you might be ready for the conversation some of us need to have right now.

But on the other hand, I think it is worthwhile to help people say that we are in uncharted territory in our relationship with the Earth and it’s not just climate change. You could look at the loss of topsoil upon which we depend. We are in uncharted territory for the acidification of the ocean. We are in uncharted territory for the loss of fisheries and fish stocks. We’re in uncharted territory for the decline of forests. We’re in uncharted territory for ice. If people are interested, it’s very easy to find out how much trouble we’re in, in relationship to the Earth. We’re also in trouble in relationship to each other. We are more divided than we’ve ever been and we have more weapons to act out our hostilities than we’ve ever had. And we don’t seem to have any individual or institution that has the capacity to bring us together unless they do it by walking on eggshells and not saying anything very significant. In other words, they can entertain us. But in terms of leading us toward unity, that’s a tougher subject. And I’m not opposed to entertainment, but it doesn’t deal with the deeper rift.

Hannah: Is there something we can be for in our worry? Does that question make sense?

Brian: Yeah. I just heard a song the other day. I wish I could remember the name of it, but it had this beautiful line in it. The singer was saying, “I want to build a bigger wolf pack so we can howl at the moon much louder.” It was something like that. It was this powerful image. And the image was, those of us who see there’s a problem, we can get together. More of us can howl louder and more. Now, howl might not be the best language for it, but here’s another way people say it. Sometimes people criticize activists. They say, “You’re just preaching to the choir.” But the fact is, the choir are the only people who are listening. So if you preach to the choir and you teach the choir to sing better and louder and more beautifully and with more emotion, then they can get the song out to more people. I feel like that is one of the most important things we can do right now. And frankly, one of the best places it happens is podcasts like yours. So that’s a big part of what you and others like you are doing, I think.

Brandon: Well, I’m glad that others have been relieved by the title because right after my stomach sank after looking at the title of your book, I experienced precisely that relief. Someone who’s just willing to name this for what it is. And I have a moderately sized family and not everyone is willing to name it quite like this. So we can’t really shift anything until we name what’s true. Your co-conspirator and a sort of mentor at a distance of mine, Father Richard Rohr, I’ve heard him describe spirituality as a long, hard look at what’s real. And so I see the title of your book very much in the tradition of naming what’s real, which is the prophetic tradition. And I wonder if you could tell us a little bit how you got to teach with Richard and what that journey was like and what your work is like these days at the living school.

Brian: Thanks so much for asking about that. It always makes me happy to talk about Richard. So back in the late 90s, I think I had read one of Richard’s books. It was called Things Hidden. It’s still one of my favorite books of his. But I didn’t know much about him. I knew he was a Franciscan and I knew he was Catholic. And things have changed a little bit, not as much as I would wish. But back in those days, Protestants stayed in their lane, Catholics stayed in their lane. So I never had any aspirations that I would ever meet Richard. But a friend organized an event and he said to me, “One of the things I’m most excited about in this event is I’m having you speak and I’m having Father Richard Rohr speak and I’ve arranged it so you overlap for one session where you’ll get to hear him speak and then you can go out to lunch together and I’ve already reserved a place for you to have lunch.” So he was like matchmaking a friendship.

So Richard and I met thanks to this wonderful friend, Spencer Burke. And over the next several years, our paths crossed. We’d both speak at an event, similar event, or we’d both be in the same town at the same time. I would contact him and say, “Hey, let’s get dinner at that Mexican restaurant down the road.” And we’d get together. And so we just kept kind of comparing notes through the years. He was interested in what I was doing with this under this umbrella of the emerging church. And I don’t know if you’ve heard, there’s a very good podcast that’s doing a little history of that conversation called “Emerged,” right now, it’s fascinating. I’m learning a lot about it even though I was involved with it. I’m learning a lot about it. And so we would meet and just compare notes.

Richard has, as of this moment, had five different kinds of cancer and is surviving all five of them. It’s quite amazing. When he had his fourth different kind of cancer, the CAC, Center for Action Contemplation, contacted me and said, “Look, Richard’s health is not good. His prognosis is not great. And would you be able to be around a little bit as an understudy if he can’t do something that you could fill in?” So that is what really ended up deepening my involvement with the Center for Action Contemplation. And since then, he got much worse in his health. But it turned it. That was the fifth kind of cancer. And that’s turned out to be quite treatable. So he’s doing amazingly well. It’s just remarkable how well he’s doing. He’s passed off the responsibilities for running the Center onto a great team of really superb staff. And then he has passed on the primary teaching responsibilities to a faculty that it’s my pleasure to be working with.

Brandon: Thank you. I’m just so thankful for that work and for the collaboration. The work you do there is just a light to so, so many people. And it’s one of the great blessings of my life to be able to share it with our students and seminarians. So just know you have a little fan club up here in the Northeast and we’re spreading the word as much as we can about all that you’re doing.

Brian: Well, thanks. And it is so relevant to this situation because what we were talking about before of this sort of a nostalgic look at the Desert Mothers and Fathers and a nostalgic look at the Celtic era of Christianity. In many ways, what Richard represents and as he, following in the path of Thomas Merton and Thomas Keating and Sister Joan Chittister and others, has been a rediscovery of some of those ancient treasures of a deep, deep, vibrant, life-sustaining spirituality in the Christian tradition.

Hannah: Gosh. Well, we’ve talked about spirituality and emotions. And I noticed you started to mention music a little bit ago. And I also noticed you’re surrounded by musical instruments. Could you tell us a little bit about how music fits into your life and work?

Brian: So, yeah, I’ve always loved music. I remember exactly when I fell in love with music. I was a kid and back in those days there were these things called LP records. And my parents bought a record of, Is it Prokofiev’s “Peter and the Wolf?” We had this little turntable and a scratchy little needle and not great speakers. But when I heard the clarinet on Peter and the Wolf, I just felt I’d been transported. And so I took piano lessons and I played a bunch of wind instruments. And then I thought I was too old to learn the guitar when I was 14, but I started playing the guitar.

Brandon: At the advanced age of 14.

Brian: I thought in order to be good at guitar, you have to start much earlier. But I fell in love with that, and then played in bands and all that sort of thing for many years. And so my spirituality has been interrelated with music, not only from singing in church and loving … I love good choir music. Not such a big fan of bad choir music, but I suppose it’s always good if people come together and harmonize and sing, so I shouldn’t complain.

Hannah: I like the idea that some people might be huge fans of bad choir music.

Brian: In my, to my very prejudiced taste, it seems that way. But anyway, I’m ashamed to say that. But I love … you know, church and music are so closely aligned. And songwriting has been a kind of spiritual discipline of mine through the years. It’s one of the ways that I sort of sit with problems or discoveries and try to celebrate them and craft them into three or four minutes.

Brandon: I have one more question, Brian. You’ve been so generous with your time, but I wonder, is there anything else that you’d like to talk about, mention?

Brian: Well, first, thank you so much for having me and for what you all are doing. You know, I have this feeling that podcasts are one of the places where the needed work that has to be done is being done. None of us know to what degree this is really a myth, but the story of Martin Luther nailing his 95 theses on the Wittenberg door, well … 95 is an awful lot. 95 is what we might call a long form nonfiction, right? He was inviting people into a deep and sustained conversation. And so much of our world is being reduced to smaller and smaller bits of attention; a fragment of attention here, a fragment of attention here. And podcasts seem to me invite people into longer conversations, which is super, super important. So I just want to say I’m grateful for what you’re doing. And I feel if we were to look at all of the amazing, good podcasts in this space that you all occupy right now, this is a wonderful sign of renaissance and you put them together and it’s more than 95 theses up on the wall.

Hannah: So maybe for our 95th episode, it should be all about Martin Luther.

Brandon: And we can mail out 95 Reeses to a winner.

Hannah: Yeah, oh, we’d have to interview our resident Lutheran. Okay, it’s all coming together.

Brandon: Well, it’s very generous of you, Brian. And I mean, we do the work together, right? We need one another and we’ll just keep, you know, being in partnership and we’ll stay connected until the hope emerges. And so our final question is always about hope. And what I’d like to do first though before I ask you about what is making you hopeful amid sort of the grim reality, I want to read the very first quote in your book. It’s in the introduction and it’s by comedian Dave Barry. And when I read this, the first three sentences, I thought, okay, this is going to be one of these books that I’m going to finish because it starts like this. And so this is comedian Dave Barry in the very first lines of your book, right? And so he writes, “So at the moment the situation appears grim and yet there are plenty of reasons to feel hopeful about the future. To name just a few:” And then in parentheses, David writes, “(Note to editor, please insert some reasons to feel hopeful about the future if you can think of anything.)” So this is your moment to supply the reasons.

Brian: Right. So I’ll tell you the chapter– the idea that really made me feel I should actually write a book about this rather than just seek therapy–was chapter six, which is called “Hope is Complicated.” I really feel that hope is necessary and hope is dangerous. There are ways that hope can really get us in trouble right now, but despair also gets us in trouble. And so it’s forced me to think more deeply about hope and that really became in many ways the germ for the book.

So here’s what I’d say. There is a phrase in the New Testament. I think it’s in Romans chapter four. It may appear elsewhere, but that’s the place I remember it. And the phrase is, “In hope against hope, Abraham believed.” And that phrase, “Hope against hope,” is something that gives me hope because it says there are times when hope fails. And so you need a hope that goes against your hope in a certain sense, a hope that transcends your normal kind of hope. And then I think of that connected to what Paul writes in 1 Corinthians 13, where he says, “Three things remain: faith, hope, and love, and the greatest of these is love.” Faith may fail, hope may fail, but love may (won’t) fail.” And when you put your hope in the power of love, it seems to me you have a kind of hope against hope. And maybe one other way to say it is, there is a kind of hope that defines itself by the likelihood of desirable outcomes. But there is another kind of hope that defines itself by saying some things are worth doing no matter how they turn out, no matter the outcome. And when we disentangle ourselves from outcomes and are committed to doing certain things because they’re right, here’s the irony. We increase the chances that those outcomes could happen because we’re not dependent on them looking super likely at any given moment. That would be a fun conversation to have with Dave Barry about.

Hannah: It would, it would.

Brandon: Oh, Reverend Brian McLaren, thank you so much for joining us. We look forward to hearing your voice again in the future.

Brian: It’s such a pleasure to be with you guys and keep up the great work.

Brandon: Thank you for listening to The Leader’s Way. We hope you were encouraged and inspired. To learn more about this episode, visit our website at berkeleydivinity.yale.edu\podcast.

Hannah: Rate and review us and follow the podcast to make sure you never miss an episode. Follow Berkeley@Yale on Instagram for quotes from the podcast and more.

Brandon: Until next time…

Hannah: The Lord be with you.