July 15, 2020

“Christian joy is inseparable from penitence, a clear conviction of Christian truth, a constant choice of the eternal in preference to the temporal, self-sacrificing devotion to those things in the community and in our own lives which are clearly in accordance with the will of God” (William Palmer Ladd, 1941).

The Present Moment

The United States and the wider world are experiencing a time of anger, of sorrow, and ultimately, we pray, of hope. While the devastation of the recent threat of COVID-19 continues, the older enemy of racism has also reared its head in unmistakable ways. So too, voices of protest and change and in particular the Black Lives Matter movement have appeared with a force unique in our time.

The Church including its seminaries (as our EDS@Union colleague Kelly Brown Douglas has recently reminded us), must face this moment both in penitence and in faith. With our bishops, and with the leaders of Yale University and Yale Divinity School, Berkeley Divinity School at Yale deplores the sin of racism in all its forms, in our daily lives and relationships, and in its systemic expressions.

Opposition to racism however cannot only mean statements about how others should act, or about the worst forms of violence performed against people of color; it is about us and our actions, past, present, and future. We must now commit ourselves afresh to addressing how racism has shaped us, and how our work of theological education must be placed in the service of bold witness to the freedom and fullness of life into which Christ calls.

A Complex Past

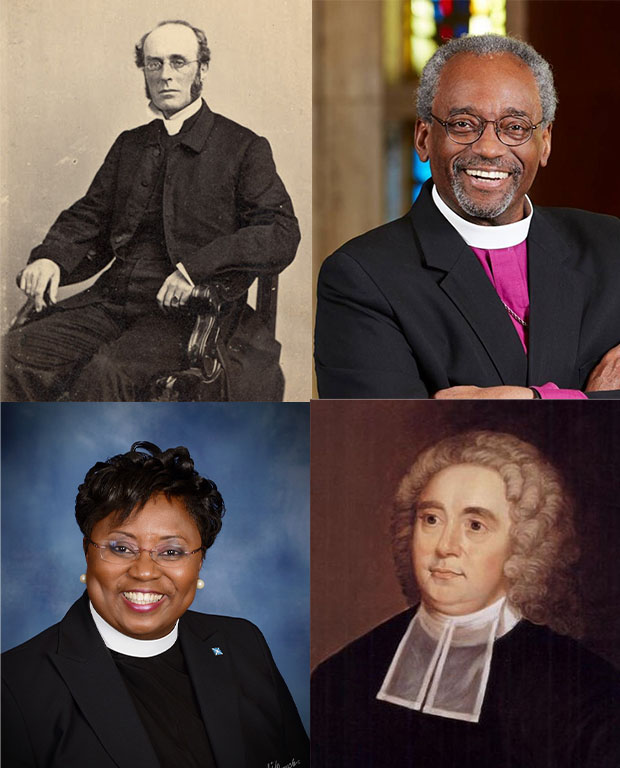

Irish philosopher and bishop George Berkeley had died a century before his name was chosen for a new theological school in Connecticut. He had a more concrete connection with Yale University during life. When his hoped-for enterprise in the New World was abandoned, Berkeley left books and property from his estate at Whitehall on Rhode Island to the relatively new College in Connecticut; his “property” included at least three slaves.

Even a century later when Berkeley was founded, New England families who were supporters of the new enterprise included slave-owners. At the consecration of the first St Luke’s Chapel in March 1861, the School’s founding Dean, Bishop John Williams, quoted Berkeley not as philosopher and bishop but as a prophet of the western hemisphere as the world’s future, Berkeley “who sang of the ‘westward’ course of ‘empire’s star,’ the star, not merely of earthly power, but of the cross and kingdom of the LORD.” Two weeks later Lincoln was inaugurated as president, and the American Civil War was about to begin.

This vision of a westward “Empire” attributed to Berkeley (reflected also in the naming of Berkeley, CA just a few years later) and the Church as its fellow-traveller, should now provoke sorrow. Such triumphalistic theology glossed over the dispossession of indigenous peoples, and assumed slavery as a means to its fulfillment. The “regions beyond” to which the School’s motto refers could easily have been misread not only as a reference to St Paul’s earnest desire to preach, but to the belief that expansion characterized by white supremacy amounted to a modern providence for the Gospel.

These stories do not exhaust the ways the School’s history is enmeshed with the attitudes and the structures that constitute racism. Our community of privileged learners has been overwhelmingly white, reflecting the wider demographics of The Episcopal Church but rarely transcending them. Most obviously, our Black alums have been as rare as they are distinguished. Our effectiveness in our singular vocation, providing leaders for the whole Church and for the whole world, and not merely for a privileged set of communities, has been limited at best. Our response to the present moment must start with penitence, and go on in faith.

A Different Future

While we have no new Chapel to consecrate this year, let this be an equally historic moment for Berkeley Divinity School. In consultation with Board leaders and other alums of color, I have proposed three areas on which to focus our efforts for change, and ask our graduates, students, supporters, friends and others to join with us in reflecting on them and helping us to act on them:

-Community

Berkeley must now use its resources to serve a diverse global Church. How will we create the diversity to which we aspire, that will allow young leaders who include people of color to discover Berkeley Divinity School as a place of welcome and inspiration? How can we recruit and support aspirants and others who will reflect this diversity? How can we identity the resources that will enable us to support them materially?

-Curriculum

Berkeley must teach and form ordained and lay leaders equipped to lead for justice and inclusion. How will our teaching and learning, and our wider formational offerings, change to reflect more adequately the complex history of the Church, the voices and contributions of people of color, and the tools needed for effective leadership?

-Symbolism

Berkeley must communicate its reality and its aspirations in symbol and substance. How do our practices of naming, displaying, and honoring various leaders, role models, or benefactors, and our particular uses of Christian symbolism reflect and create the community we aspire to?

What Now?

We must now listen, learn, and act. I invite our community to share their thoughts with the Board of Trustees as we prepare for the October meeting, to consider action plans for these three areas, and others as may arise. Please email me (andrew.b.mcgowan@yale.edu) or the Board Chair James Elrod (jimelrodjr@gmail.com), or feel free to contact other Board members with your responses and ideas. We will be offering additional opportunities to share responses in the coming months.

Please keep Berkeley Divinity School in your prayers as we explore these challenges with fresh eyes, deepened penitence, and new hope.

[With acknowledgement to Rowena Kemp ‘13 and Allyson Brundage ‘02, ‘11, for their historical research and faithful provocation.]